Neo-Mudéjar, A Spanish Architectural Style

In 1859, in a speech he made upon joining the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, archaeologist José Amador de los Ríos used the term “Mudéjar style” for the first time to describe Christian churches and palaces built using techniques and decorative elements reminiscent of those of Hispano-Islamic architecture (tiles, plasterwork, horseshoe arches, etc.). Since then, its status as a composite of all of the styles that co-existed on the Iberian Peninsula from the end of the Middle Ages has led intellectuals like Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo to consider it to be the only uniquely Spanish style that we can boast of, as they have noted that it almost immediately began to be combined with the Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance styles. The tireless quest for a distinctly Spanish style resulted, between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in the construction of bullrings, railway stations, schools, factories and homes that we now identify as examples of Neo-Mudéjar architecture.

Before we consider these impressive 19th and 20th century works, it is essential to define a list of the features that distinguish the Mudéjar style. Prime examples include the churches of San Nicolás (12th-15th century) and San Pedro el Viejo (14th century), as well as Lujanes Palace (15th century) in Plaza de la Villa, and architectural elements such as arches, vaults and doors which are held and displayed at the National Archaeological Museum. We could even head out to visit the chapel and Assembly Hall of the University of Alcalá de Henares, the synagogues of Santa María la Blanca and El Tránsito in Toledo, the Monastery of San Antonio El Real and the Alcázar of Segovia.

San Pedro el Viejo. The MAN's Neo-Mudéjar door. San Nicolás. Photos by Álvaro López del Cerro.

Main characteristics of Neo-Mudéjar architecture:

- Use of soft materials (brick, ceramic, stucco and tile) predominates over use of hard materials (stone, iron, cement).

- Exposed brick is used to achieve complex decorative patterns that cover entire surfaces with consistent geometric motifs.

- When brick is alternated with masonry (irregular stone), this is called parejo toledano (literally, “Toledo bonding”).

- Interiors are topped with ribbed vaults or coffered wood ceilings, such as that of the Church of San Nicolás.

- Ceramics –in vivid colours– feature very prominently.

- Alternating use of horseshoe, multifoil, pointed, stilted and semicircular arches.

- Despite their numerous stylistic features with Hispano-Islamic origins, buildings use elements from Christian tradition: symmetrical façades, courtyards and Latin cross plans in churches.

Arab cabinet in the Palace of Aranjuez, 1847-1851. Decorated by Rafael Conteras.

By the 1940s there were already numerous examples of Alhambresque architecture in Madrid, such as the Arab Room in the Royal Palace of Aranjuez, designed by craftsman Rafael Contreras. However, there was still no distinctly national style, but rather a Moorish revival that had spread throughout Europe and was used to decorate myriad recreational venues such as casinos, theatres and public baths, as well as buildings like synagogues.

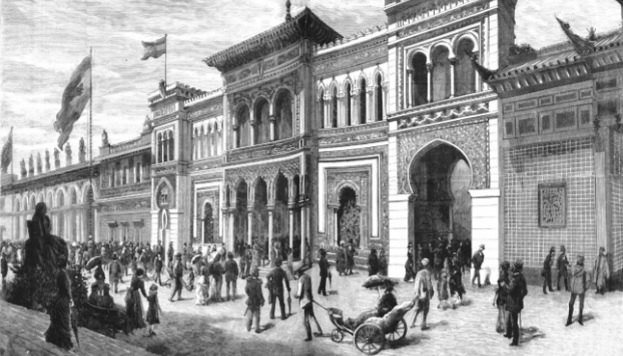

It was with the construction of the Spanish Pavilion for the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris that Neo-Mudéjar architecture began to be associated with Spain's particular idiosyncrasies. The pavilion’s façade combined elements from the Alhambra's Court of Lions with elements from important Christian buildings such as the Royal Alcázar of Seville, Puerta del Sol gate in Toledo and the Cathedral of Tarragona. Today, only a few photographs and etchings of the pavilion remain. The architect who designed it, Agustín Ortiz Villajos, also designed Madrid’s Teatro María Guerrero, an eclectic building constructed in 1885 whose interior features some Neo-Mudéjar elements, such as the coffered ceiling above the stalls. One example of this emerging architectural style, which was frequently used for performance venues in the last quarter of the 19th century, is the wall facing the main entrance of Beti Jai Fronton, built in 1894 by Joaquín Rucoba and recently restored. Unfortunately, some buildings, like the original Circo Price (1880) in Plaza del Rey and Teatro de los Jardines del Buen Retiro (1880), are no longer standing.

The seating area at the Teatro María Guerrero covered by a Neo-Mudéjar coffered ceiling. Designed by Agustín Ortiz Villajos.

Another construction that no longer stands is the Goya Bullring, which opened in 1874 on the site that’s now home to WiZink Center. Designed by Lorenzo Álvarez Capa and Emilio Rodríguez Ayuso, it was the city’s second bullring and served as a model for many others in Spain, including Las Ventas Bullring, which replaced it in 1929 and was designed by José Espelius. Most examples of Neo-Mudéjar architecture were built in the fifty-odd years between the construction of the two bullrings. After that, the style gave way to more contemporary architecture, such as the Art Deco and Rationalism of the 1930s, or to other historicist styles, such as the Neo-Herrerian architecture that emerged after the Spanish Civil War.

Las Ventas Bullring, 1929. Designed by José Espelius. Photo by Álvaro López del Cerro.

Emilio Rodríguez Ayuso also designed the Aguirre School (Escuelas Aguirre), a building in Calle de Alcalá that now houses Casa Árabe. Behind the intricately ornamental façade and tower, which might remind some of those found in Teruel, was an interesting set of spaces that were highly innovative when they first opened, in 1886. In addition to a meteorological observatory, something that was groundbreaking at the time, there was a gym, library, museum, courtyard and music room.

Neo-Mudéjar architecture was commonly used in the construction of orphanages, convents and educational and religious institutions. So many examples of this nature still exist today that it would be impossible to list them all, but some are particularly outstanding due to their size and location. These include the Conciliar Seminary of Madrid (1906) and the schools Colegio de San Diego y San Vicente (1906), Colegio de Areneros (1910), which is now Comillas Pontifical University, and Colegio de Nuestra Señora de las Delicias (1913).

Colegio de San Diego y San Vicente, 1906. Designed by Juan Bautista Lázaro de Diego. Photo by Álvaro López del Cerro.

This same period saw the construction of the churches of San Fermín (1890), Santa Cruz (1902) and La Buena Dicha (1917), the last of which has an interesting ribbed vault with a roof lantern. It was designed by Francisco García Nava, the same architect who designed the chapel and portico of La Almudena Cemetery, which opened in 1925 and features a blend of Neo-Mudéjar and Modernist elements.

The same combination is evident in works designed by Julián Marín, including Casa de las Bolas (1895) in Calle Alcalá and Madrid Moderno (1890-1906), a “colony” of small single-family houses inspired by the ideas of architect Mariano Belmás Estrada, who aimed to foster the development of cheap, sanitary housing for the lower classes. The purest examples of residential Neo-Mudéjar architecture, however, are the hotel owned by Don Guillermo de Osma (1893), which is now the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan, and the home of Don Francisco Mestre (1917), located at no. 17 in Calle Romero Robledo.

Madrid Moderno and Casa de las bolas, 1895. Designed by Julián Marín. Photo by Álvaro López del Cerro.

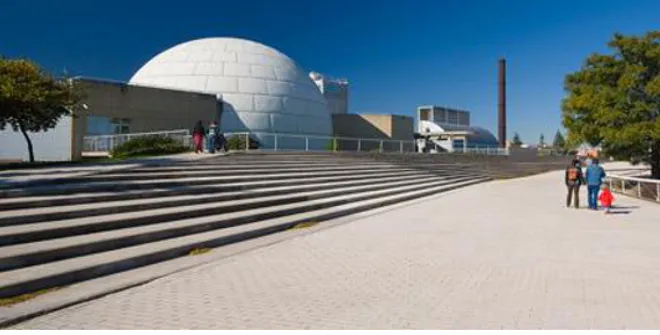

In the early 20th century, Neo-Mudéjar emerged as the style best suited to industrial architecture. Among other reasons, this was because it had turned necessity into a virtue by embracing the beauty of exposed brick and its enormous range of practical and decorative possibilities. Of particular note in this respect are the Chamberí Water Tower (1912), “El Águila” Brewery (1914), which is now the Joaquín Leguina Regional Library, the old railway training workshops that now house La Neomudéjar Cultural Centre, which has an ultra-modern serrated roof, and the former abattoir Matadero de Madrid (1925), for which Luis Bellido built multiple pavilions and an administrative headquarters (La Casa del Reloj) in what is now the largest existing complex designed in the Neo-Mudéjar style.

Matadero Madrid, 1925. Work by Luis Bellido. Photo by Álvaro López del Cerro.

Neo-Mudéjar architecture is one more example of how the 19th century reclaimed every one of the artistic styles of the past in a quest, at times schizophrenic, to find its own distinct personality. While for a century politics was shaped by the sometimes violent and traumatic transition from the old regime to the new, art focused on finding a distinct style for the world that was emerging. This was no easy task, and although at times the prefix “neo” concealed a profound lack of creativity, some of the buildings on this list are nonetheless highly innovative from a structural perspective and deserve particular attention, which we hope this post has helped to achieve.

Conciliar Seminary of Madrid, 1906. Designed by Miguel de Olabarría Zuaxabar and Ricardo García Guerete. Photo by Álvaro López del Cerro.